From fashion and street portraiture to a decade-long family archive, the London-based photographer reflects on image-making as a way of staying with people, places and memories.

Laura McCluskey first picked up a camera at 14, after choosing GCSE photography alongside art and product design. Her school had a black-and-white darkroom, where she learned the basics of using her SLR, processing film, hand-printing in trays, and the thrill of seeing her work appear on paper.

“It felt like magic,” she recalls. “I started to see life happening around me and connected it to the camera.” From the beginning, photography was a way of looking beyond her immediate surroundings and finding meaning in what was already there.

That impulse is rooted in Laura’s upbringing on the Isle of Sheppey, off the northern coast of Kent, where she spent much of her childhood at her grandparents’ house. Years later, after leaving the island and settling in London, she found herself returning – sometimes to places that appeared unchanged, sometimes to those that had become derelict or eroded over time.

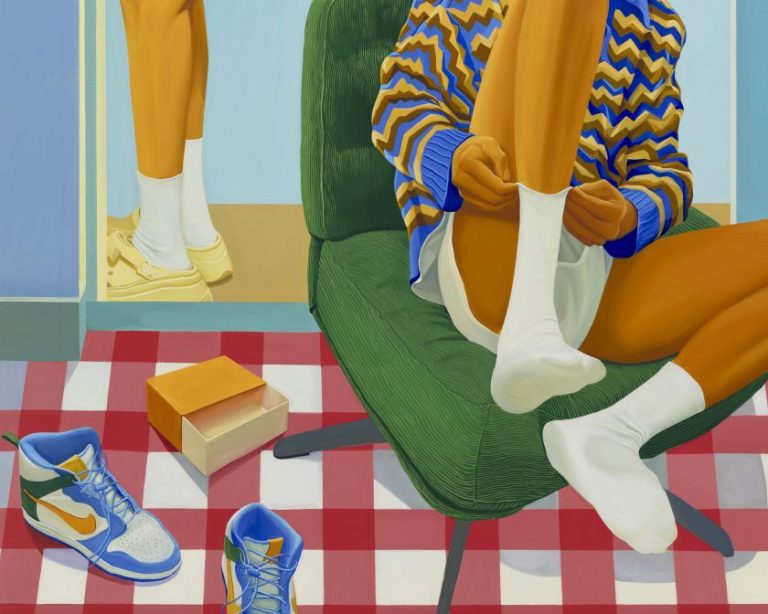

“I was drawn to using these places as backdrops,” she says. While studying at university and later working in London, Laura would cast models and shoot fashion stories back home in Kent, folding the two worlds together in the visuals.

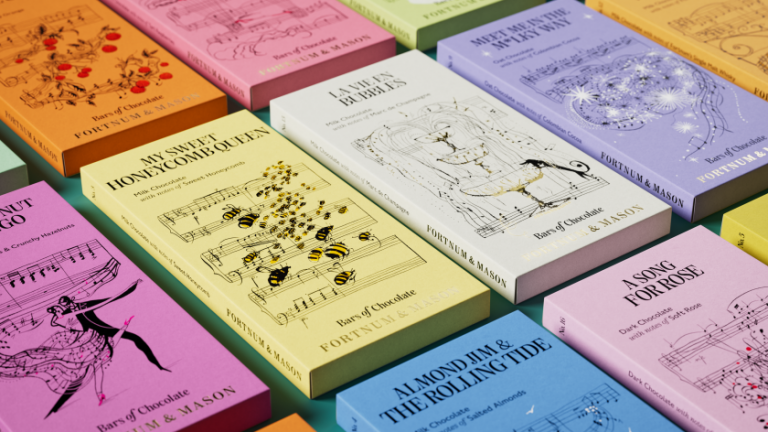

The results sit deliberately between fashion and documentary, capturing London youth culture and portraits of friends like Lexy and Pinky – caught getting ready for a drag night – with a sense of intimacy and ease that pulses through the imagery. Even in commercial contexts, such as her Loewe Flow Runner campaign shot on Sheppey, the same atmosphere is reflected in the work.

At the core of Laura’s practice is a belief in photography as a way of connecting. She seeks out interactions with the people she’s capturing, like when she takes her camera on walks around Hampstead Heath and interacts with people basking in nature and enjoying time together.

“I find it helps to set myself a goal for the day, to look for moments,” she says. Street casting has always been something she enjoys and has become an important part of her practice. “I find that most people are intrigued and enjoy the process of being directed. It’s a way of working that reminds me why I started to take photos in the first place. Creating images can be simple, and it’s just about choosing to look.”

These threads come into sharp focus in Close To Home, a decade-long project documenting her paternal grandparents, Jean and Pat, and the island they lived on.

Shot between 2014 and 2024 during each visit, and recently published as a book by Guest Editions, the work is centred on her grandparents’ house on Acorn Street in Sheerness – a place that remained visually unchanged even as time passed through it. Inside, we see sun-faded wallpaper, a vivid green carpet that looks almost like trimmed AstroTurf, comfy, unmade beds, ornaments, and fuzzy yellow curtains, lit by the sun’s golden glow.

Outside, thistle branches and laundry whip in the wind; waves thrash against the rocky shoreline; cars sit half-swallowed in overgrown thorns, while streets are frozen in nostalgia-toned hues, as if they’ve been plucked from a dream.

Most prominent, though, are the portraits of Jean and Pat. We see them cosied up in bed, sipping a cuppa and smiling at their granddaughter Laura, who’s taking their picture. The kind that can only come from closeness between the subject and photographer.

Then, as the house empties and her grandparents pass away, the photos shift and what began as a moment of being present turns into an archive – evidence of what was, long after the rooms themselves have been cleared. Below, we hear from Laura about the emotional weight of this project, what it means to document a subject so close to home, and the role photography played in navigating grief, memory and healing.

Close to Home was made over a decade – at what point did you realise it was more than a family series and needed to become a book?

Focusing on my paternal grandparents and the island’s backdrop, the work revisits physical places and childhood memories to reconnect with my family. After a turbulent family life, I’d left the island as a teenager.

As time passed, anxieties around reconnecting grew. Returning to the island felt challenging, yet the push and pull of home remained, and I sought reconnection with my family. When I’d visit, I’d take my camera, snap photos instinctively at family parties, and spend time with my grandparents, living their daily routine.

The heart of the work centres around my grandparents, Jean and Pat, who lived in the same house on Acorn Street in Sheerness. The house where my nan was born and where she lived her whole adult life. Decorated decades ago, her unique, eccentric style became the backdrop for the work.

As time stood still for the house itself, my grandparents grew older and documenting their changing way of life felt important. To share moments and confront mortality together, as they experienced the end of their lives. Over time, I saw this act as a way to connect, get closer, and remain present.

Alongside this, I’d drive around the island, revisiting places from my childhood and spending time in nature. Facing what felt challenging by capturing postcards of a memory and collecting moments from the past.

The project came to a natural end after my grandparents passed away, and the house itself was emptied for sale. I spent time photographing each room, empty yet rich in history. The act of getting closer and looking beneath had an intense healing effect, and so much of the work began to make sense intuitively. I decided to make a book to bring these moments together for my family and for myself.

What was your process like, and were there moments you struggled with or resisted continuing?

I shot with the same cameras throughout. Keeping things simple and mostly shooting with available light. Capturing moments as they happened and exploring the house and garden. My grandparents enjoyed the process and loved having their portraits taken. As I shot them, they would tell me funny stories about their lives, or my nan would sing to me.

My nan Jean was creative in her own way and encouraged me to follow my own path. I had a strong sense to keep going and make the work, I knew it was something that I was doing for myself. It was the later editing and processing of the work that were the most challenging.

The work is so rooted in memory, place and family ties – how did your relationship to your grandparents and to Sheppey shape the emotional language of these images?

The process of making the work was completely instinctive, driven by a subconscious need to return home and reconnect. I see now that I was placing myself back in my family by documenting where I’m from. The emotional language of the work has been shaped by love, healing, and acceptance.

There’s often an expectation to draw from personal history or work ‘close to home’ – but in reality, that can be emotionally complex. What did you find most challenging about turning something so personal into a body of work?

I didn’t start shooting with any expectation of a long-term project or that I would shoot it for as long as I did. It became a way of being that allowed me to remain present and develop a new relationship with my family as an adult. To be able to spend more time physically in a place that had held so much tension. Alongside documenting my grandparents, I’d drive to places I’d spent time as a child, walking the beaches and being in nature to quietly reflect.

As I shot, I’d return to London and process the film. Occasionally, printing an image; most often, storing the negatives in a box for the future. I knew my grandparents wouldn’t be around forever, and I didn’t want to force a narrative for a project or think about the work with any timeline or goal.

After a decade of shooting, the work came to a natural end with the passing of my grandparents and the sale of the house. It was then that I found closure in completing the work. I spent the following year looking through everything I had shot, spending time in the darkroom printing.

This was more emotionally challenging than making the work: looking back, trying to process what it meant to me, and grieving the loss all at once. I found journaling helpful for unpicking my why. Why I’ve made the work and what I was trying to say. It made me realise the power of the subconscious and how important it is to be guided by intuition in creativity. It surprised me, 10 years later, to learn what I had done.

How has making this work changed the way you see home and memory – and what do you hope viewers sit with after spending time with it?

I’m still processing what the work means to me, and I think that will be ongoing. It has been a catalyst for difficult conversations with my family and has allowed me to accept my background. I think the work has allowed me to connect with my younger self and, at the same time, let go. I appreciate the connection and love I’ve experienced, too. Themes of relationships, memory and loss are universal, and I hope that people can see themselves in the work.

Are there themes or projects you’re hungry to explore next – maybe something that Close to Home has opened up for you creatively?

The work has allowed me to connect with my purpose as an artist and to see my work in a new light. I want to continue to make work with feeling.