Nengi Omuku. Photo credit – Full house Partners ©

The Nigerian artist explores colourful connections between people and flora, inspired by her mother and former career as a florist.

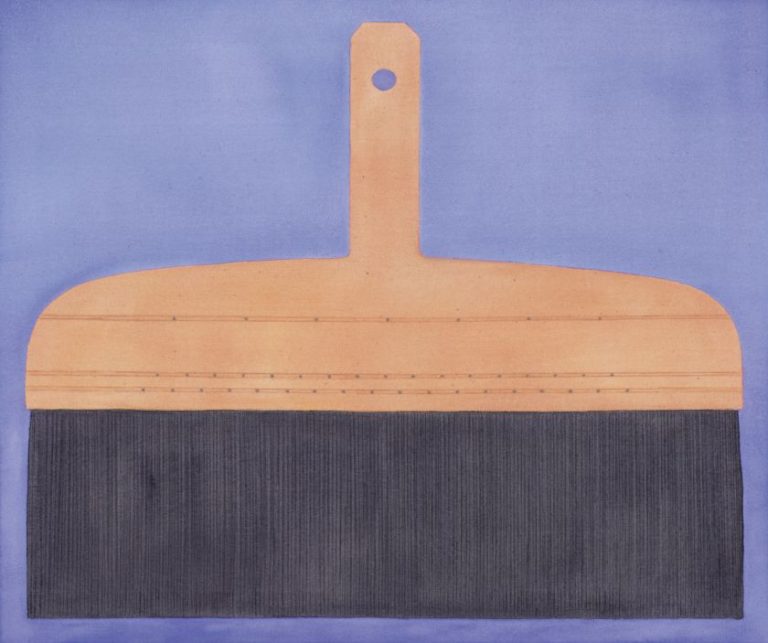

Born in Warri, Nigeria, Nengi Omuku has been making a name for herself through a distinctive style of painting. This involves applying oils to gesso-prepared composite strips of sanyan, a tightly woven, hand-spun fabric that has played an important part in Nigeria’s cultural history.

The dichotomy between the intricately woven and carefully designed materials, combined with the fluidity of the oil paint, speaks to living between cultures while at the same time feeling deeply connected to her country of birth.

Although Nengi attended art school in London, she currently lives and works in Lagos, one of the world’s biggest megacities with a population of 16 million. But right now, she’s back in Blighty for the opening of her first major UK solo exhibition, The Dance of People and the Natural World, at Hastings Contemporary. We chatted to her about the rising popularity of Nigerian art, her love of nature, and working in a psychiatric ward.

Dynamic and vibrant

While Nengi is glad to be back in the UK again, she couldn’t be happier living in Nigeria’s capital right now. “The art scene in Lagos is incredibly dynamic and vibrant,” she enthuses. “Our art community is tightly knit and continues to grow rapidly, especially with the increasing number of individuals pursuing art as a profession. In response, we are witnessing the emergence of various institutions, such as art fairs, galleries and museums, actively contributing to the flourishing art scene. It’s truly an exhilarating time.”

Her work has previously appeared in a New York exhibition, Dissolving Realms, curated by Katy Hessel, an art historian and writer focusing on women in art and addressing their under-representation. So we ask whether Nengi feels she’s been held back by her gender in any way.

“I haven’t personally experienced any barriers due to my gender in Nigeria,” she responds. “Initially, when I started having exhibitions in Lagos, some people who saw the work assumed that the paintings were created by a man, which I found amusing. However, I didn’t perceive it as a significant barrier to showcasing my work. Overall, I haven’t encountered any specific obstacles or limitations related to my gender in terms of exhibiting or any other aspects of my artistic career.”

Nengi Omuku ‘Eden’, 2022 credit Pete Jones

Nengi Omuku installion view with ‘Days Gone By’, 2022 credit Pete Jones

South London Gallery recently presented the exhibition Lagos, Peckham, Repeat: Pilgrimage to the Lakes, looking at the connections of Peckham, sometimes known as ‘Little Lagos’ and its larger namesake in Nigeria. Yinka Shonibare is a big name in the art world, and Yinka Ilori is also on our radar. So, is Nigerian contemporary art having a moment, or has the UK just been slow to acknowledge the country’s creative force?

“I won’t describe it as a moment for us,” says Nengi. “Art created by Nigerian artists has been thriving for centuries. If we consider ancient works like the Benin Bronzes and Nok Terracottas, they predate colonisation and demonstrate the rich artistic heritage of Nigeria.

“Additionally, we have notable modern masters like Aina Onabolu, Ben Enwonwu, and Uche Okeke who contributed to the development of Nigerian art,” she adds. “Even today, contemporary artists are making their mark both locally and internationally. The Nigerian art scene has always been vibrant throughout our history, even before the geographical location was called Nigeria. However, it seems the international art community is now beginning to recognise and appreciate this.”

Love for nature

As the title of her show suggests, her love for nature is a common element in Nengi’s work. “One of my earliest and most cherished memories of home is a vivid image of my family, particularly my mom, tending her garden,” she says. “My mother, being a horticulturist, established the first garden centre in Port Harcourt, where I grew up in Nigeria. This image of my family and the captivating greenery has always provided me with a sense of safety and comfort.”

Nengi Omuku ‘Lighthouse’, 2021 credit Pete Jones

Nengi Omuku ‘Repose’, 2022 credit Pete Jones

She adds: “In my artistic practice, I often delve into themes of inner turmoil and the psychological realm, aiming to speak about experiences of conflicts, unrest, and individual or collective trauma. Over time, my creative exploration expanded to include moments of solace and relief. I discovered that landscape painting offered me a unique avenue to express these emotions that could not be conveyed in any other way. Consequently, incorporating landscapes into my artwork became a natural choice.”

For Nengi, landscape painting serves a dual purpose. “On one hand, it allows me to position individuals within tranquil and harmonious environments where they can find respite. On the other hand, it acts as a therapeutic outlet for my mind, as I find solace and peace by painting flowers and plants.”

Cinematic painting

On display at the show is her largest work to date, Eden, 2022. Measuring over 5m in width, it’s a cinematic painting hung from the ceiling away from the wall, allowing viewers to look behind it.

“Sanyan is a precolonial textile from Nigeria, traditionally crafted by the Yoruba people,” she explains. “It is made by blending silk from moths and industrial cotton to create threads, which are then woven into small panels. These panels are stitched together to make dresses that women wore during ceremonies and special events.”

It is significant for Nengi to exhibit the majority of her paintings away from the wall, similar to how one would display a tapestry, as this reflects the original objecthood of the fabric. “Before I paint on the textile, I reverse the stitches to ensure I paint on the back of the tapestry, allowing the original embroidery to remain visible,” she explains. “This act ensures that the painting doesn’t overwhelm the existing textile.”

Nengi Omuku ‘Red Velvet’, 2022 credit Pete Jones

“Hanging the artwork this way also helps viewers see the original fabric and gain a glimpse into Nigeria’s rich and vibrant precolonial history,” she adds. “The art of weaving is just one small aspect of our diverse heritage.”

Hospital work

Today, Nengi’s work is in public and private collections worldwide, including the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami; Baltimore Museum of Art; Women’s Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, Cambridge; and The Whitworth, Manchester. But these are not the only places where his work can be viewed.

She’s also installed one of her artworks in a psychiatric ward as part of her work with the art-in-mental-health charity Hospital Rooms. “The painting was installed in a locked intensive care psychiatric ward to provide a creative and uplifting environment for the patients,” she explains. “I will be creating another mural with them next year in a hospital in Norwich, which I am eagerly looking forward to.

Nengi Omuku ‘Welcome Home’, 2022 credit Pete Jones

“It is important to me to bring art outside of traditional museum and gallery settings and into spaces where access to art may be limited,” she adds. “Inspired by the work of Hospital Rooms, I am involved in a similar project in Nigeria with TAOH (The Art of Healing), where we install art by local and international artists in psychiatric wards in Lagos. These opportunities, alongside having my work featured in permanent collections in museums worldwide, are incredibly exciting to me.”

Also on her to-do list is an upcoming show in December at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in Palm Beach. Following that will be her first solo show in New York with Kasmin Gallery, scheduled to open in September 2024.

Nengi Omuku: The Dance of People and the Natural World is on at Hastings Contemporary until 3 March 2024. Find out more at www.hastingscontemporary.org.