California-based illustrator, artist and letterer Sam Rodriguez specialises in creating portraits that include the “unseen aspects of individuals.” We caught up with him to hear how they’re made and the ways in which graffiti shaped his process.

Some people have always known that they wanted to be artists. But for others, the realisation has been more subtle. This was the case for Sam Rodriguez who, despite drawing since he was a toddler, first became aware that art was a habitual tic around the age of 12 when he started doing graffiti.

“It was exactly what I needed and helped me avoid being in an unstable home,” he tells Creative Boom. “More importantly, I found a group of friends that I fit in with. There’s something about graffiti that feels like a nervous tic, and it brought me comfort and escape. I did this until my early twenties, eventually replacing it with art school and work.

“I decided to become a professional illustrator when I was 19 where I had worked part-time for a national news wire in San Francisco. There, I met journalists, graphic designers and illustrators who exposed me to the industry.”

Inspired by a diverse range of artists, including Prince, Frida Khalo, Barry McGee and Norman Rockwell, to name a few, Sam began developing his own signature style. “I was inspired by Prince because of his stubborn dedication to being original and for having such a range in his music,” Sam explains.

“Barry McGee for showing the world that Graffiti was just as legit as other genres. Frida Khalo for her surrealism and depth. Barron Storey (who was also my professor in college) for introducing me to Visual Journalism and the art of storytelling. Milton Glaser for mixing abstract shapes with faces, and Norman Rockwell for his compositions and ability to render cultural landscapes.”

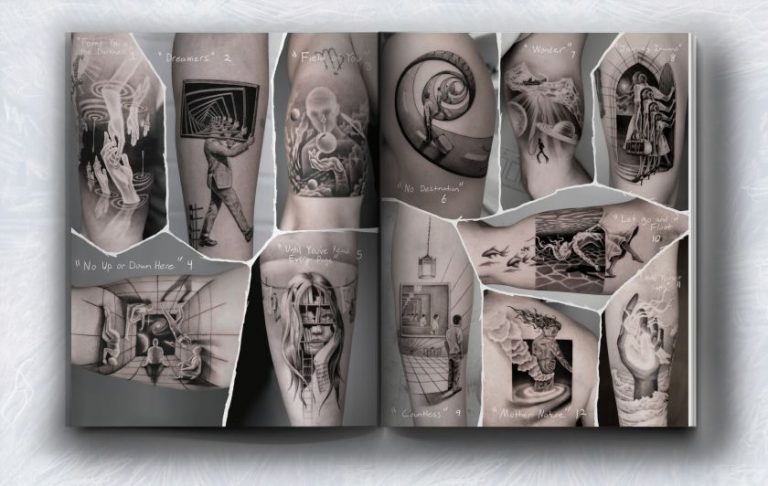

All of these influences come together to shape Sam’s style, in particular his favourite art form, portraits. “I love how portraits tell a story,” he reveals. “The face is a composite of physical features and expressions that tell us about emotional states, time, and identity. Facial expressions are one of our oldest means of communication, and for an artist, this language allows for endless exploration.”

Sam goes beyond simply capturing a likeness though. His portraits also capture the unseen elements which make up a person. “Each of us goes about our existence in a dualistic way,” he says. “We explore the world through our material senses, but we also have our thoughts, interests, and memories.

“These are the unseen aspects that emerge when we get to know others. I like to imagine how a person would look if we could see them in their entirety at a certain moment.”

As well as portraits, Sam is also known as an illustrator and typographer. To help keep himself organised, he breaks his work down into three categories: nouns, verbs, and typography. These bring a sense of order to the chaos of creativity and allow him to focus on the art at hand.

“It enables me to discover the voids I need to fill,” he says. “For the longest time in recent years, I’ve been strongly focused on portraiture. However, there was a period in my early twenties where I had worked on figurative pieces and am now revisiting this. I looked at my portraits and realised that I needed to zoom out and see how these characters could interact in bigger scenes. I was motivated to expand.

“There’s a difference in storytelling through a portrait versus an active figure and I don’t want to miss out on exploring both. It’s easy to lose perspective when I’m not self-reflecting so I think of the categories as my table of contents, helping to examine the macro view of my work. There is no real separation but it is a useful navigation tool.”

Tying together all of Sam’s disciplines though is his background as a graffiti artist, which he says provided him with the foundation he still uses today. “It was a culture that demanded self-motivated pro-activity,” he says. “I learned about artistic expression, the importance of personal style and taking risks. Today I’m so much more tame compared to that period but I still implement many habits from then.

“One example is how we used to do various forms of graffiti. For example, Tags were faster markings that acted as advertisements of ‘I was here’ versus the more elaborate Production Pieces that involved a group of people forming concepts for a large-scale wall.

“I draw the comparison in the present to Tags being like quick social media posts and production wall Pieces being like project collaborations with big clients. It’s self-promotion mixed with making something in a bigger collaborative effort.”

Personal style was also very important in the graffiti world, with people ready to be disrespectful of artists if they copied another’s style. And while Sam admits that this is an extreme reaction, it’s an ethos he still sees some value in.

“The biggest influence from that era in my life was the risk-taking aspect,” he concludes. “At that time, I risked incarceration and personal safety just for the sake of making art. This is probably why it didn’t feel like a big risk when I decided to become a career artist.

“That risky part of graffiti will always be with me, and it’s a reminder that I’d be an artist whether I was paid or not.”