Comfort food is often based on treats that remind us of home. Photographer David Fletcher has an ongoing love for the Staffordshire Oatcake, a local delicacy of Stoke-on-Trent that he wanted to pay homage to in a new photo series.

No matter where we call home, we’ll never forget where we grew up. Those familiar streets and people, the experiences we had, make us who we are. We might be happier in our new location, but there is always a pull to “home” – a hunger for nostalgia, comfort, and the things we consider part of our roots.

For photographer David Fletcher, that’s the humble Staffordshire Oatcake from Stoke-on-Trent. If you’ve never heard of it, it’s a local delicacy of the Potteries. A sort of savoury pancake that you can’t find anywhere else in the world. “It’s a unique regional food, only found today in and around North Staffordshire,” says David. “It is a kind of savoury pancake – not hard like the more familiar Scottish oatcake – and about the size of a small dinner plate. It is traditionally eaten for breakfast, typically with bacon and cheese. Never made at home, it is bought from your local oatcake shop, each with its own closely-guarded recipe.”

The small shops David speaks of are almost always family-run, some of which have been in the same family for generations. “I know of one which has been in the same family since 1934. If a shop is sold, the recipe is part of the deal,” he says.

Growing up in Stoke-on-Trent, the oatcake was part of David’s life, and it was only when he moved away that he realised they weren’t available elsewhere. “Trips home may have been notionally undertaken to visit relatives and friends, but the purchase of oatcakes to bring home for the freezer was always part of the itinerary,” he says. “Not the same as fresh, but an adequate substitute when needs must.”

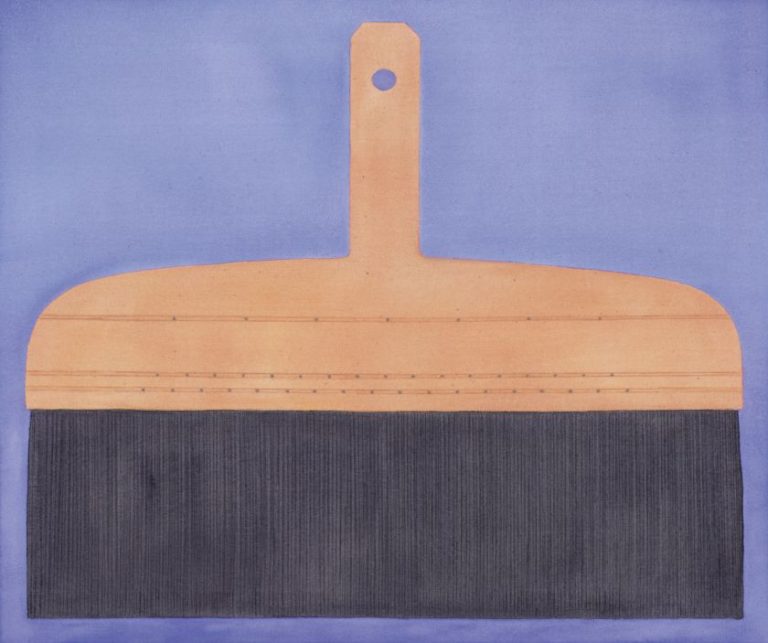

Oatcakes are cooked on a griddle and traditionally hand-poured, but some shops have retro-fitted ingenious machines to pour the mixture, each one crafted to fit the existing grill. “These machines come from a tradition of precision engineering in the Potteries which complimented the pottery, brick-making, steel and mining industries,” David continues, “a tradition which produced the designer of the Spitfire by Reginald Mitchell.”

Oatcakes can be purchased plain to use at home (make mine with cheese and pepper, please), but the griddle means shops can add and cook various fillings for those wanting to eat on the go. You can choose from traditional bacon and cheese to black pudding and beans. “It provides a kind of fast food ideal for sustaining the hard labour of workers in heavy industries,” David says.

Today, David is an award-winning documentary photographer based in the New Forest. When he began this project to document Stoke’s oatcake shops, he thought he might be recording a disappearing world but was delighted to discover that they’re still flourishing. “As well as the bricks and mortar, I wanted to capture the oatcake-making process and, importantly, the people on both sides of the counter. This story is little known outside Stoke, so I wanted to spread the word,” he says.

Covering all the oatcake shops in a Stoke-on-Trent postcode he’s aware of, David would love to know of any he might’ve missed. He has enjoyed meeting the people behind each location and would happily document more. “Oatcake shops are not just places to buy food; they are a social phenomenon. I also found shops that have been part of the same Stoke family for generations. I found one run by a woman from Latvia and one by a woman from Poland who is married to an Italian. Another shop has a champion darts player, the owner’s brother, making the oatcake mix.

What makes the oatcakes so special to him? “The localisation of the shops makes the whole story of Staffordshire oatcakes special – if Stoke was in France, I feel sure they would have their own protected status like Brioche Vendéenne or Pâtes d’Alsace. They are unusual in a world of fast food in that they are hand-made and sold fresh. But the most important thing is that they taste so good.”

As a “Stokie in exile”, David has definitely appreciated his roots as he’s got older, like many of us. “I suppose our spectacles become more rose-tinted as we age,” he says. “As the first generation in my family to go to school beyond 16, let alone go to university, I have grown to appreciate too what opportunities my parents and grandparents opened up for me. At 18, we are in a hurry to escape our hometowns and look for greener grass, but when I return to Stoke now, the strength of the memories evoked is like a physical force.”

David’s first experience of photography was with his father in a home darkroom and later in the studio of a Burslem printworks, where he rose from apprentice to manager. Other careers “got in the way”,” but he has since returned to photography professionally following an MA in Documentary Photography at the University of Westminster. Other recent documentary projects include New Forest Commoners, the Irish Border, and absentee slave-owners.

He says of his latest project on Stoke-on-Trent: “It’s not a pretty place, but it has a powerful, somewhat forgotten history. As well as being a leader of the world-renowned Stoke pottery industry, Burslem-born Josiah Wedgwood was a key figure in the 18th-century Midland Enlightenment along with engineers Matthew Boulton and James Watt, chemist Joseph Priestley and physician Erasmus Darwin. Leading advocates of the abolition of slavery, Erasmus and Josiah were the grandparents of Charles Darwin. Writer Arnold Bennett and designer of the Spitfire, Reginald Mitchell, were also sons of Stoke. Perhaps the oatcake can help to lead a Staffordshire renaissance!”